Social Determinants of Health and Survival in Humans and Other Animals

Abstract

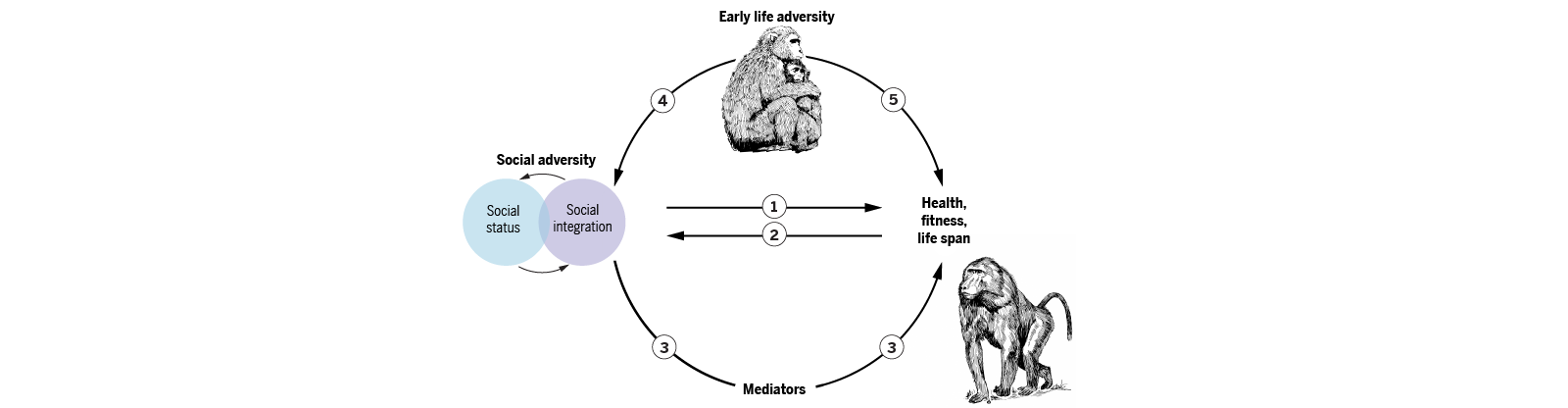

The social environment, both in early life and adulthood, is one of the strongest predictors of morbidity and mortality risk in humans. Evidence from long-term studies of other social mammals indicates that this relationship is similar across many species. In addition, experimental studies show that social interactions can causally alter animal physiology, disease risk, and life span itself. These findings highlight the importance of the social environment to health and mortality as well as Darwinian fitness—outcomes of interest to social scientists and biologists alike. They thus emphasize the utility of cross-species analysis for understanding the predictors of, and mechanisms underlying, social gradients in health.

Structured Abstract

BACKGROUND

The social environment shapes human health, producing strong relationships between social factors, disease risk, and survival. The strength of these links has drawn attention from researchers in both the social and natural sciences, who share common interests in the biological processes that link the social environment to disease outcomes and mortality risk. Social scientists are motivated by an interest in contributing to policy that improves human health. Evolutionary biologists are interested in the origins of sociality and the determinants of Darwinian fitness. These research agendas have now converged to demonstrate strong parallels between the consequences of social adversity in human populations and in other social mammals, at least for the social processes that are most analogous between species. At the same time, recent studies in experimental animal models confirm that socially induced stress is, by itself, sufficient to negatively affect health and shorten life span. These findings suggest that some aspects of the social determinants of health— especially those that can be modeled through studies of direct social interaction in nonhuman animals— have deep evolutionary roots. They also present new opportunities for studying the emergence of social disparities in health and mortality risk.

Advances

The relationship between the social environment and mortality risk has been known in humans for some time, but studies in other social mammals have only recently been able to test for the same general phenomenon. These studies reveal that measures of social integration, social support, and, to a lesser extent, social status independently predict life span in at least four different mammalian orders. Despite key differences in the factors that structure the social environment in humans and other animals, the effect sizes that relate social status and social integration to natural life span in other mammals align with those estimated for social environmental effects in humans. Also like humans, multiple distinct measures of social integration have predictive value, and in the taxa examined thus far, social adversity in early life is particularly tightly linked to later-life survival.Animal models have also been key to advancing our understanding of the causal links between social processes and health. Studies in laboratory animals indicate that socially induced stress has direct effects on immune function, disease susceptibility, and life span. Animal models have revealed pervasive changes in the response to social adversity that are detectable at the molecular level. Recent work in mice has also shown that socially induced stress shortens natural life spans owing to multiple causes, including atherosclerosis. This result echoes those in humans, in which social adversity predicts increased mortality risk from almost all major causes of death.

Outlook

Although not all facets of the social determinants of health in humans can be effectively modeled in other social mammals, the strong evidence that some of these determinants are shared argues that comparative studies should play a frontline role in the effort to understand them. Expanding the set of species studied in nature, as well as the range of human populations in which the social environment is well characterized, should be a priority. Such studies have high potential to shed light on the pathways that connect social experience to life course outcomes as well as the evolutionary logic that accounts for these effects. Studies that draw on the power and tools afforded by laboratory model organisms are also crucial because of their potential for identifying causal links. Important research directions include understanding the predictors of interindividual and intersocietal differences in response to social adversity, testing the efficacy of potential interventions, and extending research on the physiological signatures of social gradients to the brain and other tissues. Path-breaking studies in this area will not only integrate results from different disciplines but also involve cross-disciplinary efforts that begin at study conception and design.